Jostle

22.5. – 12.7.2025

at Galerie Elisabeth & Klaus Thoman, Vienna, AT

22.5. – 12.7.2025

at Galerie Elisabeth & Klaus Thoman, Vienna, AT

“At least you’ll never be a vegetable, even artichokes have hearts,” says the eponymous protagonist in Amélie (2001) to the nasty greengrocer. The sharp-tongued remark was whispered to her from an imaginary prompter in a basement window. Amélie’s act of defiance is not only directed against the grocer’s chauvinistic jokes, but also against her own passivity in this recurring situation. Support comes quite literally from the background: an opening in the backdrop of the Parisian street scenery. Sarah Bechter’s first solo exhibition at Galerie Elisabeth

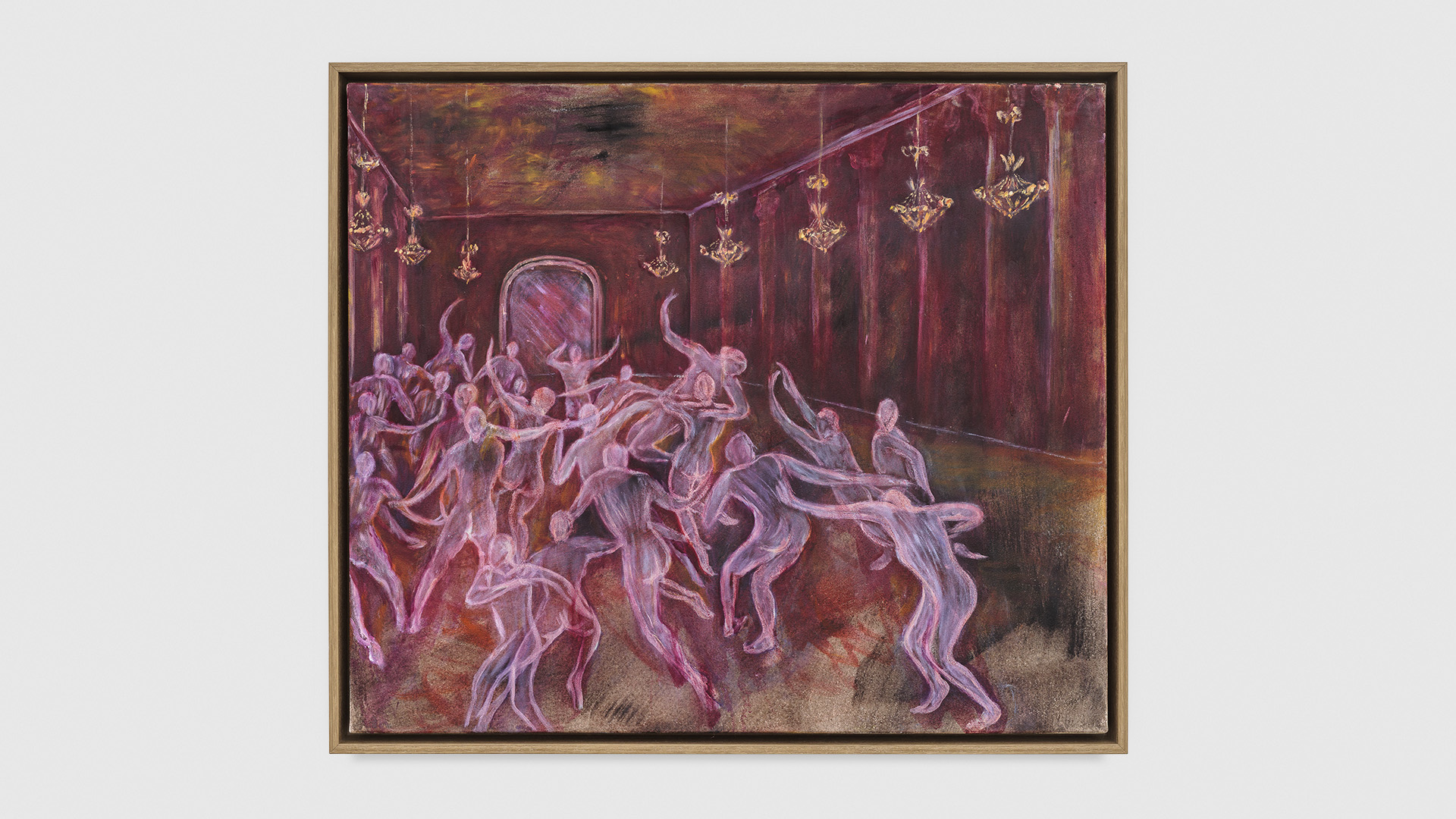

& Klaus Thoman also refers to a situation in which one must assert oneself. The English title Jostle describes the experience of being pushed or shoved, as well as the state of a crowd in a confined space, thus capturing both an individual experience and a social constellation.

While “jostle” conveys a sense of overabundance, the figurative paintings are characterized by a dual emptiness. The figures do not assert themselves within a densely populated pictorial space but rather against a backdrop in which they threaten to dissapear. Moreover, in some areas of the composition painted in pigment, ink, and oil paint, the canvas emerges, shifting the focus from subject matter to painterly technique. In Unbalancing This Structure (2025), for example, both moments can be observed: In front of a firmament of blues, violets, and reds, a solitary figure—barely distinguishable from the background—balances on a balustrade. While the fantastic flickering and weightlessness suggest a dreamlike scene, the schematically indicated architecture of the dome frames the painting’s relation to reality. At the apex of the dome, the so-called oculus, the canvas is exposed, bearing only the muted tone of the pigment mixed into the gesso during the priming process. In the diptych Throwing Gestures At Each Other (2025), a representative piece of architecture similarly adorns the backdrop of the picture. Here, the figures facing each other are not falling or floating; rather, they appear to have been propelled to the edges of the picture by a force emanating from the empty center. Between them lie only artichokes, as associated at the beginning, which are a symbol of wealth. Here, they become pawns in the competition for attention and recognition in the art scene. Every exchanged gesture, however, carries the risk of sacrificing of a part of one’s heart.

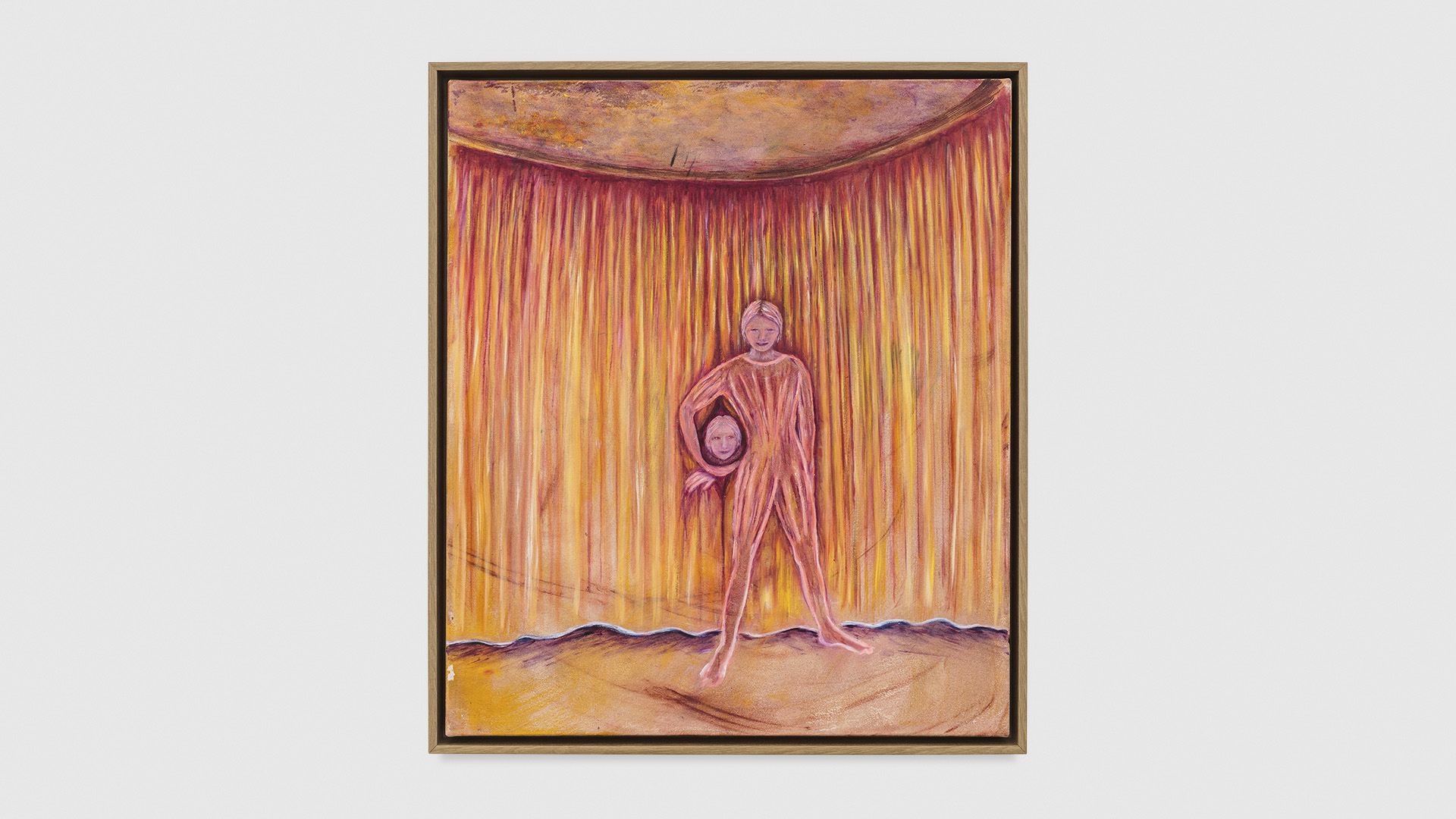

Sarah Bechter’s painting is self-aware, as can be seen, for example, in the way the gesticulating duo seems to lean naturally against the edge of the picture. In Framing It For You (2025), the figure itself becomes the architecture: A Titaness framing the empty archway at the center of the image. This ambivalence between figure and ground, between actor and backdrop, between subject and social context, is not only characteristic of Sarah Bechter’s painterly idiom, but also points to the feminist stance articulated through it. The corporeality of the androgynous beings is contained entirely in the painterly gesture that brings them forth—namely, the brushstrokes from which they are constructed. Sinewy, semi-transparent figures who are neither granted to recede behind illusionism nor to dissolve into abstraction. Contrary to Georges Bataille’s concept of “l’informe,” which understands the formless as a plunge into the corporeal and obscene—a liberating act from the constraints of bourgeois society in the early 20th century—feminist psychoanalyst Luce Irigaray does not see it as a transgression, but rather a reproduction of the category of the Other as something inconceivable and unstructured. For Irigaray, the formless does not lie outside a phallogocentric system: rather, it often functions as its blind spot—a site where the feminine is not articulated but silenced. She therefore does not call for the dissolution of form, but for the creation of new symbolic orders in which female subjectivity can speak autonomously: “To be born, for a woman, would mean to be able to emerge from the hells, the gulfs and abysses, the oceans and the ice/mirrors… That act, necessarily willed and active on her part, would allow her to accede to the light-for herself and for the other-within a finite and in-finite horizon, a space of breath and gestation which is not the void.” 1

The abstract paintings in the exhibition correspond to the idea of such an initial undifferentiation, as described by Irigaray in the quoted passage. These small-format works are characterized by the same fantastical color spectrum as their figurative equivalents, though here it is dominated by submarine blues and rusty violets. The flowing, torn, and at times gaping compositions originate in ink that Sarah Bechter applies directly onto the canvas. Scenes emerge from this preconscious painting using oil paints, where color and figuration meet at the threshold of representation. The faces that surface are both euphoric and characterized by longing and horror —and they find their echo in the impression they leave on me as a viewer. In both series presented in the exhibition, the painterly process, which does not begin with a blank canvas, can also to be read metaphorically: A female artist’s work is never unmarked, but always already defined by attributions, social constructions, and limitations. Jostle responds to this immensity and counters it with a space that is not the void.

1 Luce Irigaray: “A Natal Lucuna” in: Women’s Art Magazine, Nr. 58, London, 1994, translated by Margaret Whitford, p. 11–13, here p. 13.

All installation views © Galerie Elisabeth & Klaus Thoman / kunst-dokumentation.com

While “jostle” conveys a sense of overabundance, the figurative paintings are characterized by a dual emptiness. The figures do not assert themselves within a densely populated pictorial space but rather against a backdrop in which they threaten to dissapear. Moreover, in some areas of the composition painted in pigment, ink, and oil paint, the canvas emerges, shifting the focus from subject matter to painterly technique. In Unbalancing This Structure (2025), for example, both moments can be observed: In front of a firmament of blues, violets, and reds, a solitary figure—barely distinguishable from the background—balances on a balustrade. While the fantastic flickering and weightlessness suggest a dreamlike scene, the schematically indicated architecture of the dome frames the painting’s relation to reality. At the apex of the dome, the so-called oculus, the canvas is exposed, bearing only the muted tone of the pigment mixed into the gesso during the priming process. In the diptych Throwing Gestures At Each Other (2025), a representative piece of architecture similarly adorns the backdrop of the picture. Here, the figures facing each other are not falling or floating; rather, they appear to have been propelled to the edges of the picture by a force emanating from the empty center. Between them lie only artichokes, as associated at the beginning, which are a symbol of wealth. Here, they become pawns in the competition for attention and recognition in the art scene. Every exchanged gesture, however, carries the risk of sacrificing of a part of one’s heart.

Sarah Bechter’s painting is self-aware, as can be seen, for example, in the way the gesticulating duo seems to lean naturally against the edge of the picture. In Framing It For You (2025), the figure itself becomes the architecture: A Titaness framing the empty archway at the center of the image. This ambivalence between figure and ground, between actor and backdrop, between subject and social context, is not only characteristic of Sarah Bechter’s painterly idiom, but also points to the feminist stance articulated through it. The corporeality of the androgynous beings is contained entirely in the painterly gesture that brings them forth—namely, the brushstrokes from which they are constructed. Sinewy, semi-transparent figures who are neither granted to recede behind illusionism nor to dissolve into abstraction. Contrary to Georges Bataille’s concept of “l’informe,” which understands the formless as a plunge into the corporeal and obscene—a liberating act from the constraints of bourgeois society in the early 20th century—feminist psychoanalyst Luce Irigaray does not see it as a transgression, but rather a reproduction of the category of the Other as something inconceivable and unstructured. For Irigaray, the formless does not lie outside a phallogocentric system: rather, it often functions as its blind spot—a site where the feminine is not articulated but silenced. She therefore does not call for the dissolution of form, but for the creation of new symbolic orders in which female subjectivity can speak autonomously: “To be born, for a woman, would mean to be able to emerge from the hells, the gulfs and abysses, the oceans and the ice/mirrors… That act, necessarily willed and active on her part, would allow her to accede to the light-for herself and for the other-within a finite and in-finite horizon, a space of breath and gestation which is not the void.” 1

The abstract paintings in the exhibition correspond to the idea of such an initial undifferentiation, as described by Irigaray in the quoted passage. These small-format works are characterized by the same fantastical color spectrum as their figurative equivalents, though here it is dominated by submarine blues and rusty violets. The flowing, torn, and at times gaping compositions originate in ink that Sarah Bechter applies directly onto the canvas. Scenes emerge from this preconscious painting using oil paints, where color and figuration meet at the threshold of representation. The faces that surface are both euphoric and characterized by longing and horror —and they find their echo in the impression they leave on me as a viewer. In both series presented in the exhibition, the painterly process, which does not begin with a blank canvas, can also to be read metaphorically: A female artist’s work is never unmarked, but always already defined by attributions, social constructions, and limitations. Jostle responds to this immensity and counters it with a space that is not the void.

1 Luce Irigaray: “A Natal Lucuna” in: Women’s Art Magazine, Nr. 58, London, 1994, translated by Margaret Whitford, p. 11–13, here p. 13.

All installation views © Galerie Elisabeth & Klaus Thoman / kunst-dokumentation.com